In 1877, Thomas Edison in the United States and Charles Cros in France independently conceived of a machine that would convert sound waves into grooves on a cylinder. In Cros’ idea, a device called a paleophone would trace sound waves onto a soot-covered glass plate; this tracing would then be converted into an etching on a glass cylinder. In Edison’s version, sound waves would be traced directly onto a foil-covered brass cylinder.

Edison patented his invention and created a prototype before Cros, and thus became known as the inventor of sound recording. Over the next decade, his invention received various refinements: cylinders were made from a variety of materials (wax, cardboard, celluloid), flat discs were used as a new shape for sound carriers, and amplifying horns were added to the machines to magnify the sound during recording and playback.

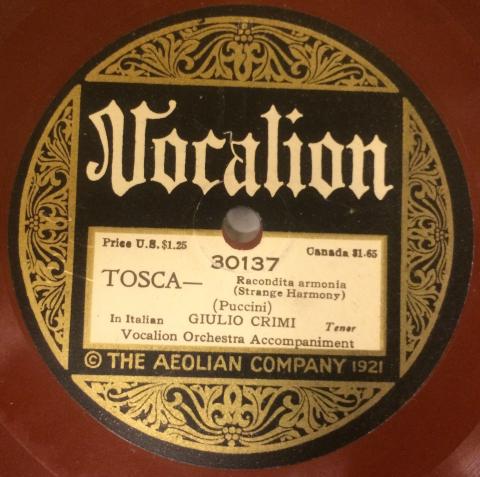

Grooved media (the technical term for sound recordings created by a needle etching into a surface) has since come to include a huge range of sizes, colors, and shapes. Records and cylinders have been made from shellac, metallic soap, aluminum, various brands of plastic (vinyl being perhaps the most famous), chocolate and bubblegum. Though record companies often claimed that these various innovations were meant to improve sound quality or durability, in actuality their effectiveness was more in marketing the recordings to new audiences.

A current case exhibit on the third floor of the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts features a selection of grooved media recordings from the Rodgers & Hammerstein Archives of Recorded Sound. Celebrating the 140th anniversary of the inventions of Thomas Edison and Charles Cros, the exhibit showcases the range in size, shape, and substance found among grooved recording formats.