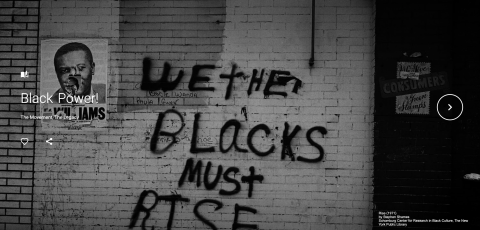

The concept of Black Power was first introduced by Stokely Carmichael, leader of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, and fellow SNCC worker Willie Ricks during a Civil Rights “March Against Fear” in Greenwood, Mississippi, in June 1966. Like no other ideology before, the multiform and ideologically diverse movement shaped black consciousness and identity and left an immense legacy that continues to inform the contemporary American landscape.

Between 1966 and 1976, numerous cultural, political, social, and economic programs were developed by a diversity of formations with various ideologies. Together, these organizations, as well as the periodicals they published and the arts they created, galvanized millions of people in the broadest movement in African-American history.

Perceived mostly as a violent, urban episode that followed the largely rural, non-violent Civil Rights movement, the Black Power movement has been eclipsed in the general public’s memory by its precursor. Yet the Black Power era, which lasted only ten short years, had a more significant impact on issues of identity, politics, culture, art, and education than any prior movement in African-American history. Black Power’s impact is still felt today in ways that have become so woven into the national fabric that few recognize them as the legacy of this youth-led movement.

Black Power was a global phenomenon. Reaching beyond America’s borders, it captured the imagination of anticolonial and other freedom struggles across the world, and was also influenced by them. Marginalized populations rallied around slogans fashioned after “Black Power,” and organizations modeled or named themselves after the Black Panther Party. Similarly, the Black Power aesthetics of natural hair and African inspired fashion, and the concept that black was beautiful, resonated throughout the country and beyond. Following in the Black Power movement’s footsteps, American-Indian, Asian, Latino, women’s, and LGBT groups challenged the status quo, and the politics of group identity entered mainstream academia and society at large.

One of the lasting legacies of the Black Power movement has been the enduring strength of the Black Arts movement. Writers and artists in dozens of cities assembled and fashioned alternative institutions. Kwanzaa, a creation of the Black Power movement, has been part of mainstream America for decades; and the cultural transformations brought forth by the movement have left indelible marks on black aesthetics and visual arts, as well as on hip hop and spoken word artists.

Thus, to understand twentieth and twenty-first century African-American history, and ultimately American society today, it is imperative to grasp the depth and breadth, the achievements and shortcomings, and the enduring legacy of the Black Power movement.

---

Photo Credit:

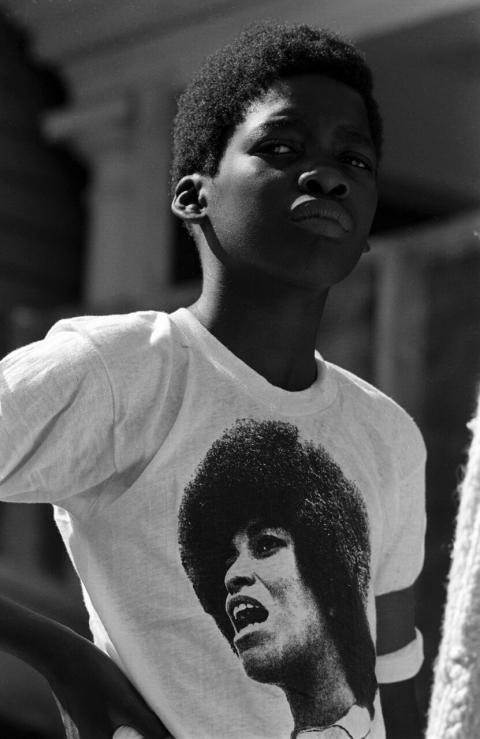

On August 18, 1970, Angela Davis was the third woman to be placed on the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted Fugitive List. She was charged with supplying the guns that George Jackson’s seventeen-year-old brother, Jonathan, used in a failed attempt to free three black prisoners in August 1970. Her trial was one of the most famous court cases in the United States and was followed throughout the world. Individuals and organizations created items to wear in support of her freedom and innocence. Oakland. 1972 © Stephen Shames.

Anti-imperialism march on African Liberation Day, Washington DC, May 1974. © Risasi Zachariah Dais.