Section 2: The Children

“Not far from Nuremberg, in a small country, a king and queen rejoiced over the birth of a beautiful baby girl whom they named Pirlipata. But the princess had been born under a dark cloud for Dame Souriconne, the Queen of the Mice, had vowed to cast a spell on the royal couple’s first born.

“The king sent to Nuremberg for the famous inventor, Drosselmeyer, to devise a means of ridding the palace of all the mice. But the threat of the Mice Queen was carried out. One night, the six guardian nursemaids and their six cats fell asleep, and the spell was cast. One of the nursemaids awoke just in time to see the Queen of the Mice running from the Princess’s cradle. She sounded the alarm, but it was too late. The despair was great indeed when they beheld what had happened to the delicate and charming Pirlipata. Her eyes had lost their heavenly hue, and had become goggle, fixed, and haggard. Her little mouth had grown from ear to ear; and her chin was covered with a beard like grizzly cotton. Her head had become enormous and mis-shapen, and her body deformed and ugly.

“On pain of his life, Drosselmeyer was commanded to break the spell. He consulted the Court Astrologer who consulted the stars. The spell would be broken if the princess ate the kernel of a Krakatuk nut. But the nut, the shell of which was so hard that a cannon could pass over it without crushing it, must be broken in the presence of Princess Pirlipata by a young man who had never been shaved and had always worn boots.”

(Leabo, from the Alexandre Dumas père version of the story by E.T.A. Hoffmann.)

Although the above story might not be familiar to most ballet goers, it is the prologue that sets the entire narrative of The Nutcracker in motion. A young man who had never been shaved and had always worn boots is located and he duly cracks the Krakatuk and breaks the spell on Pirlipata. However, while her beauty is restored in the cracking action, the young man’s handsomeness is stolen from him in return and now he is the one with the enormous head and cotton beard. Repulsed, Pirlipata rejects her gallant Nutcracker, who accepts his fate silently and awaits the day when his spell will be broken. Audiences familiar with the ballet know the rest. The Nutcracker is given to a young girl named Mary who falls in love with him. He rescues her from the Mouse King and is restored to his human form.

Balanchine was clear about his desire to return to the original source material for his interpretation of the story, and in reading the above passage one gains an understanding of the dark tonal mood underpinning the frothy fun of Candy Land that sits merrily on the surface of the performance. For although W.H. Auden wrote that ballet cannot express memory, George Balanchine’s The NutcrackerⓇ is indeed a poignant journey into the past for Balanchine, recalling his childhood, his early experiences as a dancer, his family, and, most of all, his innocence.

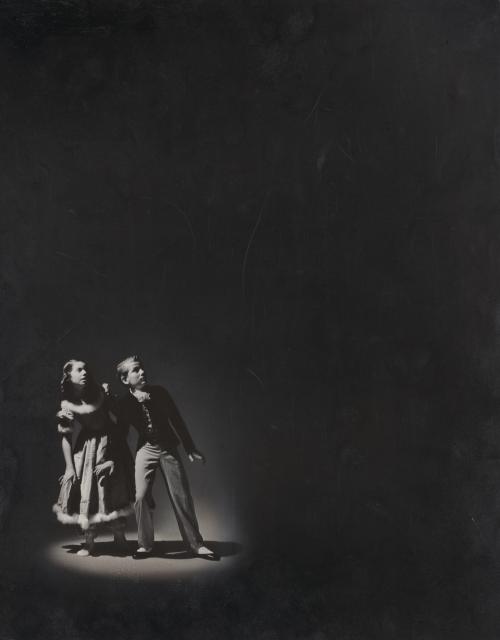

The role of the child is central to The Nutcracker, and the scale of the world (adult-sized mice and a 41-foot Christmas tree) is designed to pull the audience into the perspective of children encountering the world around them. The twin experiences of fear and wonder that are central to the life of a child are echoed in Balanchine’s interpretation of The Nutcracker, which alternatively bathes Mary in darkness and light in her quest with the Nutcracker Prince.