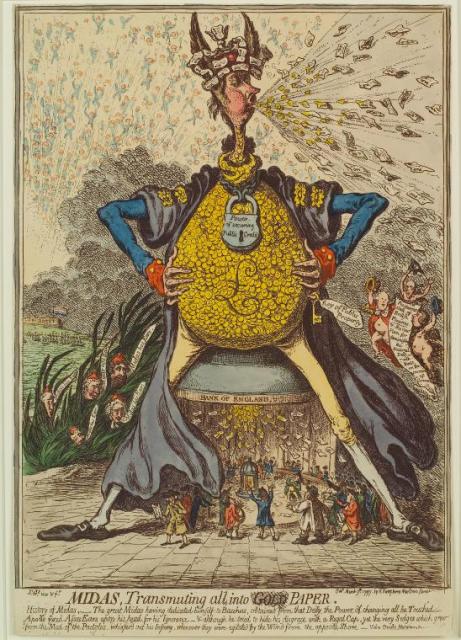

James Gillray (British, 1756–1815), Midas Transmuting All into Paper, 1797, Hand-colored etching and engraving, Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints, and Photographs

Afterlives

The South Sea and Mississippi Bubbles reverberated throughout the eighteenth century, an age of fierce colonial rivalry and recurring economic crises for both England and France. The bubbles left their mark culturally and politically too. They gave rise to a public possessed of an irrepressible appetite for both economic news and financial satire. Echoes of the 1720 crash resounded at the end of the century, when both governments began printing paper money on a large scale, ushering in new waves of optimism mixed with distrust. Throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, periodic financial meltdowns elicited similar responses from artists who drew upon many of the same motifs and characters that appear in The Great Mirror of Folly—such as the toppling Icarus or the world-bearing Atlas, to whom banking titans were often compared. In 1907, for example, The New York Press published a cartoon representing American financier (and New York Public Library patron) J. Pierpont Morgan as “The Atlas of Finance,” simultaneously celebrating and lampooning him for having rescued his country from economic ruin.

More recently, contemporary commentators like the British artist Grayson Perry have mobilized historical phrases and imagery—not unlike the printmakers of The Great Mirror of Folly—to explore the cyclical nature of financial crises and the long, painful shadows they cast. In our own era of blockchain and newfangled financial instruments such as bitcoin, it isn’t too hard to understand the impulse of The Great Mirror of Folly’s satirists to want to visualize and make sense of such bewildering realities, or alternately to revel in the chaos, fear, and desire that they unleash.