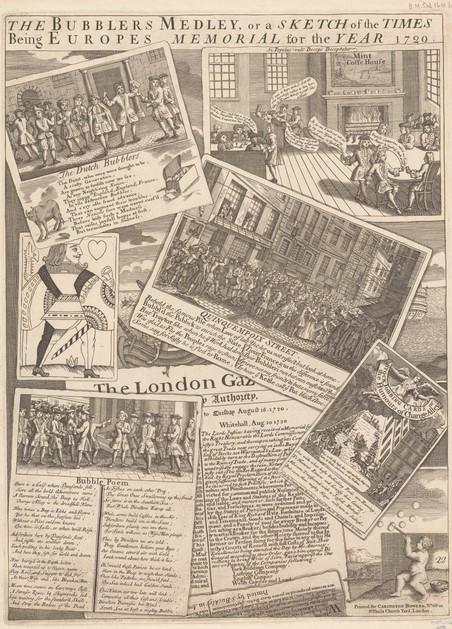

Anonymous; The Bubblers Medley, or a Sketch of the Times: Being Europe’s Memorial for the Year 1720; 1823 (restrike of 1721 plate); Etching and engraving; Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints, and Photographs

Empire of the Imagination

The Mississippi Bubble marked the arrival of what appeared to be an economic miracle in France. Seemingly overnight, insolvency gave way to prosperity. In Paris, dizzying affluence occasioned a building spree, as well as the coining of the words nouveau riche and millionaire. Driving such transformation was the introduction of a new currency: paper money. France’s banknotes, issued in lieu of metal coinage, were backed by projected profits in New World commerce. Between 1719 and 1720, France’s credit skyrocketed. Under John Law’s supervision, the Company of the West absorbed the entirety of the kingdom’s foreign enterprises. Rechristened the Company of the Indies, this vast, state-run conglomerate merged with the Royal Bank, rendering France’s credit inseparable from the fortunes of its corporate empire.

The bubble that Law orchestrated quickly spread throughout Europe. As in France, England had its creditors swap their debt for stock ownership in the state’s trading corporation. Anxious to safeguard the South Sea Company’s soaring value, in early 1720 England restricted the growth of competing corporations and caused investor confidence to plunge. But the bull market charged on, migrating to the Netherlands, where the vogue for publicly-traded insurance and other maritime ventures took hold. By this time, France was paying the price for having flooded the kingdom with banknotes well in excess of what it could redeem in coin. Within months, critics like the French philosopher and novelist Montesquieu were skewering the speculative economy as “an empire of the imagination.”