Section 5: Set Concepts

New York City Ballet moved into the New York State Theater (recently renamed the David H. Koch Theater) in April 1964. Balanchine, who had always had an emotional attachment to The Nutcracker, which evoked for him remembrances of the grand classical ballets he had seen and performed in at the Mariinsky, was determined to showcase the ballet properly now that he was no longer constrained by the capacity of City Center, where the original 1954 production had been performed. In a 2014 Vanity Fair article, the former timpanist Arnold Goldberg goes so far as to say that Balanchine had the stage of the State Theater built expressly to be able to work with the technical specificities of the Christmas tree that he had in his imagination for his production of The Nutcracker. When producer Morty Baum queried the cost and need for the tree at all, Balanchine replied that “The Nutcracker is the tree.”

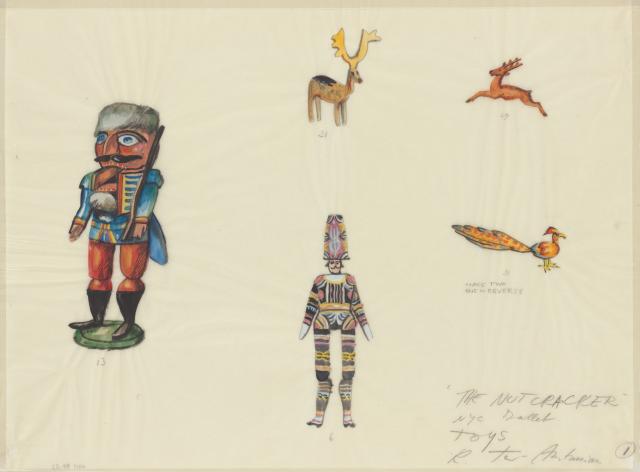

Designers Barbara Karinska and Rouben Ter-Arutunian lavished attention on the new production. Karinska, who by 1964 was working exclusively for New York City Ballet thanks to a Ford Foundation grant, revisited the costumes that she had created for the original 1954 production, mainly adding embellishments. Ter-Arutunian, on the other hand, was replacing Horace Armistead as set designer, and he obsessed over every detail to make a ballet on the epic scale that Balanchine was striving for. Like Balanchine, who drew on his memory of Christmases past for the ballet, Ter-Arutunian seems to have tapped into his Armenian childhood for inspiration to build the world of The Nutcracker. Even though the tone of Act I is Germanic, the color scheme is Eastern European, with yellows and blues dominating. Equally, the food on the Christmas tree and the use of fruit in Candy Land evokes Slavic traditions.

George Balanchine’s The NutcrackerⓇ was one of only five full-length ballets that he choreographed. These evening-length productions stand in stark contrast to the work that Balanchine is best known for, which reduces costumes to leotards, and removes sets from the equation entirely. The influence and impact of the set and costume designs on the dancing itself is not to be underestimated. It affects pacing, direction of movement, extension, and formation. Without the work of Karinska and Ter-Arutunian, it is hard to conceive of a successful Act I, which relies so heavily on mime, in a space as large and imposing as the State Theater. Ter-Arutunian’s sets frame the action, but also interact with it, filling out the world for the audience, as in the snowy forest where Mary and her Prince must travel alone. Equally, Karinska’s costumes evoke a sense of time and place, which gives each scene a painterly quality and realistically situates the dancers, no matter how fantastical their location becomes.